I took my first film photo in 2013. It was summer I think. I bought my Canon AE-1 off of eBay thinking that somehow, film photography is, in many ways, better or more respectable than digital photography. The picture wasn’t special; the bougainvillea (مجنونة / جهنمية) tree in our yard. The edges of the photograph were burnt and the green was saturated (something I came to appreciate in some colour films). For some reason, that picture never left my mind. I still think about it. What drove me to have this specific tree as my first ever film photograph? I don’t really know. Throughout the years I would continue going back to that same tree, as a constant representative to how I started photography.

The idea of film elitism didn’t come up from thin air for me. The internet is littered with websites, blog posts, and forum discussions touting the inherent superiority of film. That somehow, digital censors would never recreate the same feel or warmth of film images. In a way, that is true. Film, as a medium, has this amazing power of nostalgia over people. A reminder to when they were children shooting a family vacation with a disposable camera. The results, too, were different from digital photographs. I don’t know if it’s nostalgia or the chemical structure of film emulsions, but for some reason, these pictures did look better. The analogue feel of film gave them a sense of life; a physicality that elevated its quality. This piece is neither a condemnation or condoning of film; I still shoot film exclusively on my cameras (except for when I shoot with my iPhone). But the idea of why I shoot film has certainly changed throughout the years.

Going back to the idea of film elitism, I bought the idea of film being the inherently pure photographic medium. That, because I shoot film, my photography is automatically better than those who shot digital. That us vs them nature continued for a long while in me. Even tagging the photos I posted with#film, #filmisnotdead, or #(whatever camera I used to shoot that photo). This, being an open letter to my younger self, is why I can say that I was full of shit. Utterly. I was so convinced by my superiority as a photographer that I forgone any effort of improving my skills or developing as a photographer. I relied on my self made unicorn status, demanding appreciation from online followers because I shoot film. For a while, that concept of superiority defined my identity as a photographer. That identity was further perpetuated by constant pretentiousness. One of the most poisonous mantras in photography is Henri Cartier Bresson’s (the father of street photography and co-founder of Magnum) the decisive moment. The decisive moment is a concept that first appeared in his book by the same name. In the book, Bresson talks about that perfect split second where you press the shutter button at the perfect time and take the perfect photo. That split second would mean the difference between a good photo and a bad one.

Bresson surely showed that concept in his photos. For example, of the man jumping over a puddle or the picture of the man on a bicycle in Paris. As gorgeous as these photos are, they are not the decisive moment. There is no such thing as a decisive moment. Looking at Bresson’s contact sheets, he worked the scene (taking multiple photos of the same subject from different angles and times). Bresson was a genius not because he knew when that decisive moment was, but because he employed his training as an artist to help him work the scene and study the geometry of photography. But, Meshari from years ago didn’t know that. He was so full of himself that, more than once, proclaimed to only take one or two photos of a subject maximum as if it’s a matter of pride; vehemently believing in the decisive moment. Meshari misunderstood the decisive moment. It was not a stroke of luck or the right timing. More than anything, Bresson’s decisive moment was simply a truism explaining the spontaneous and unexpected beauty of street photography. You don’t wait for the decisive moment, you create it. If only Meshari, years ago, got his head out his ass and realised that.

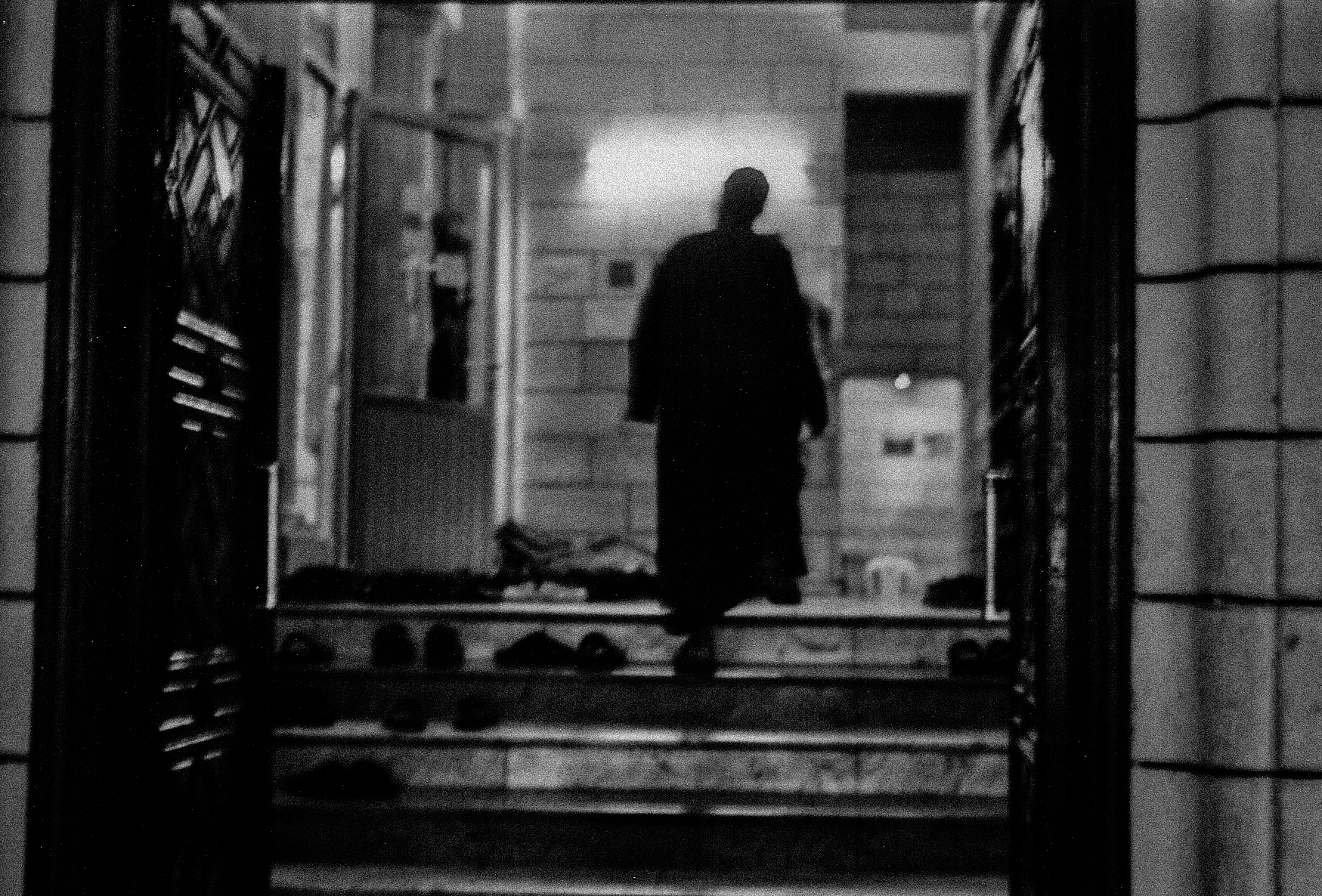

The pretentiousness didn’t stop there. I remember reading Roland Barthes’ gorgeous book Camera Lucida. That book, without a shadow of a doubt, is one of my favourites when it comes to photography. I often find myself going back to it every few months. Thing is, that’s not what I took out the book years ago. I was convinced in rooting my very amateur photography with my embarrassingly lacking philosophical knowledge. Why? It made me seem smart on Twitter and Instagram. I started talking about photographing in black and white because it brought out the inherent feeling of loneliness and alienation within people, or, it showed the true nature of the world: a dichotomous purgatory of bodies floating past each other. Basically a whole bunch of rubbish I’m pulling out of my ass. A chronic ass pulling condition. I looked down upon colour photography because it was to mainstream, too “populist”. Again, refer to the medical case above. It wasn’t black and white photography alone. This pretentiousness also extended to me looking down upon my photographer friends and acquaintances who didn’t not follow my foot steps and *air quotes* photograph the human condition *air quotes*. Can you feel the rage at such pretentiousness build up in your heart? I know. Drink some water.

All these things I did back then were annoying, but that’s not why I’m writing this. I’m writing this to talk about the effect all this had on me. The belief in film superiority, the pretentiousness, the pseudo-intellectualism, whatever you might want to call it, made me dislike photography. I was toxic towards my own passion. I put these invisible limitations on myself — limitations perpetuated by my own desire for ego and affirmation — to the point where I started disliking going out and taking photographs because I expected my work to embody a certain philosophical or artistic criteria. Showing off and pretending to be someone I’m not just for a couple of likes on Instagram or Twitter retweets jaded me from the one thing that mattered to me the most in photography: having fun.

I had a conversation with this person sometime back (that person is me. I talk to myself a lot. Making up an anecdote just makes for better writing. And makes me seem less alone. Okay, okay continue reading), and that person asked me: why do you prefer shooting in black and white? Two years back I would’ve went on this speech regarding the artistic merits of monochromatic photography. But I just thought to myself for a second and said, because I know how it works, and more often than not I just feel like it. I’ve shot so much black and white film that I now, more or less, gotten used to how it works and how to shoot it well. That doesn’t mean I don’t love colour films. Sometimes I feel like shooting colour, or sometimes I’m going to a beautiful colourful place that shooting black and white would just be unfair. That was my answer (again, to myself. Just wanna make the point of me having long conversations with myself clear). This is what I realised mattered to me the most in photography: having fun. Of course I won’t act holier than thou and pretend that I don’t care about my ego. I do. Big time. It feels amazing for your work to be loved by people and being appreciated and having exposure. But that ego balances out with simply enjoying the act of photography. To not be limited by self imposed limitations and setting bars so high that they’re impossible to reach, disheartening you from working at all.

Looking back, I don’t even understand why I felt so elitist towards film. For God’s sake, I sometimes take better photos with my iPhone than my Leica camera. Funny story, I saved up for a Leica for about a year and a half. At first I was so convinced that having a Leica camera would make me a better photographer. That I would use the same camera as my photographic idol used: Josef Koudelka, Bruce Gilden, Abbas, Winograd, etc. Half way through the saving up process I realised how utterly childish of me thinking that was. I was halfway through being able to afford the Leica so I thought why not just continue saving up for it. I’d buy it as a way to treat myself (since, before that, I haven’t really bought something that expensive to treat myself before) and just enjoy using it.

I made the decision to switch to mainly digital once I move back to Kuwait since it won’t be feasible to shoot exclusively on film if I’m living there. It’s never about the gear, it’s about the result. Cameras are just tools like a screwdriver or a phone. They are a means to an end, not the end itself. A Leica is a gorgeous piece of engineering, but it’s no better than my Nikon F3 or the camera on my phone.

I might be pontificating (I’m just looking for an excuse to write that word) in this post, but I am an amateur photographer. Nothing more than that; a reminder I keep telling myself. I realised that if I’m not enjoying photography, there is no point in doing it at all. Not for fame or groundbreaking artistic endeavour, but enjoyment; self fulfilment. Photography is a catharsis to me. Suffering from depression and anxiety, it is a hobby I can lose myself into and focus on the simple joys it brings me, focus on the many friendships it nurtured for me. I no longer take a certain photo or focus on a certain subject because of a deep intellectual reason, but because I like the way it looks, the colours, faces, framing, etc. It all boils down to this one simple fact. I burned many photos and ruined many rolls in my time doing photography and will do so for years to come. The beauty of it is that it is a continuous learning process; an ongoing exploration of the craft. Last winter, I went back to that tree in our yard and photographed it. Somehow automatically like a religious rite. It was the same. Never changing. Only I did, and I’ll continue doing so.

So here’s what I want to say to my fellow photographers or people who want to get into photography: there are no rules, there are no manifestos. Just go out there and enjoy it. That’s all that matters.

Oh, and for pretentious past Meshari: bitch you ain’t Bresson.

***

Note: Most of the photographers mentioned in this post can be found in Magnum Photographers' archive.